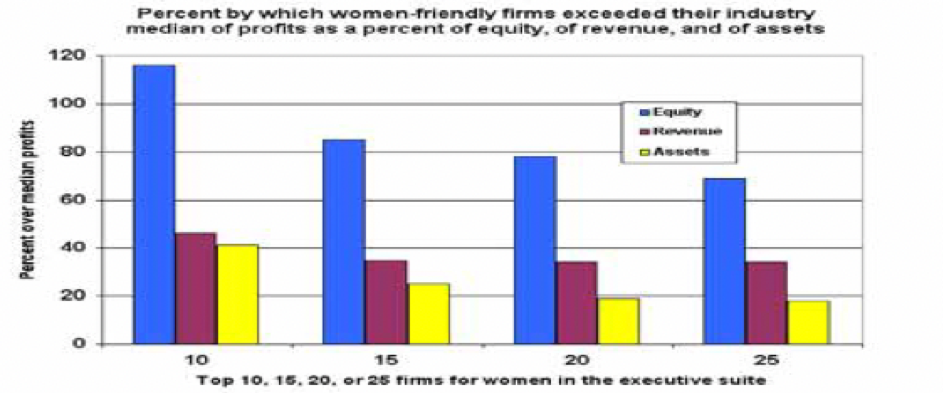

An extensive 19-year study of 215 Fortune 500 firms shows a strong correlation between a strong record of promoting women into the executive suite and high profitability. Three measures of profitability were used to demonstrate that the 25 Fortune 500 firms with the best record of promoting women to high positions are between 18 and 69 percent more profitable than the median Fortune 500 firms in their industries.

Women in the Executive Suite Correlate to High Profits

The glass ceiling issue is one of the most emotional managerial issues of the past decade. Although a great deal of anecdotal evidence exists, there has been very little empirical work to support even the most basic contentions concerning the issue. One of the areas most in need of evidence involves profitability. It is alleged that firms that have had a good track record of promoting women to the executive suite have found that practice to have been profitable, but there is little empirical evidence that the assertion is, in fact, true.

In order to test that assertion, we evaluated the record of 215 Fortune 500 firms concerning the inclusion of women in the executive suite for the 19-year period from 1980 to 1998. A point system was devised, and the top 25 firms for women were then evaluated on three different measures of profitability relative to the median Fortune 500 firms in their industries for 1998. All three measures demonstrated that higher scores were correlated to higher profitability.

Previous Studies

Since the mid-1980s,

advocates for women have worked hard to convince the business world that women

are as capable as men in high executive positions, and that their inclusion in

the executive suite would contribute greatly to the success of a company. The

pioneering book in this area was Morrison et al.’s Breaking the Glass Ceiling,

which brought the term ”glass ceiling” into the lexicon in 1987. This

work was based on interviews with 76 executive women, and was qualitative in

nature.

Other books followed. John

Naisbitt argued that the presence of women in upper levels of the organization

would be beneficial, and Driscoll and Goldberg used in- depth interviews to

examine the lives of senior women executives. Helgesen argued that women have a

largely untapped advantage in leadership style and that women’s leadership

styles transform organizations, but none of these excellent books reported

quantitative evidence of profitability.

The Fact-Finding Report of

the Glass Ceiling Commission was a report of the perceptions of women in the

workplace, and did not attempt to connect the presence of high-ranking women

executives to profitability for their corporations. Furchtgott-Roth and Stolba

provided a guide to the economic progress of women and, since 1985, the

advocacy group Catalyst has issued over 30 excellent research reports on

various aspects of progress for women, but none of them have addressed the

issue of profitability with empirical evidence.

There are at least three

reasons why the study was not attempted earlier. First, there have been only a

handful of firms with women in upper level positions, so that it was difficult

to make a valid statistical comparison between the very small number of firms

with influential women and the huge number of firms without them. Expanding the

base number of women-friendly firms was not easy because it was very difficult

to learn which firms had women in the executive suite at levels just below the

very visible positions of President or CEO. Finally, although longitudinal data

is widely regarded as the most solid, it is not often done because the data is

very difficult and time consuming to collect.

Fortune 500 Data

Our study took advantage of

a very large base of Fortune 500 data we collected for the period 1980 to 1998.

The study began in 1992, when each Fortune 500 firm was invited to supply us

with data about the number of women in their top 10 executive positions, the

next 10 executive positions, and the Board of Directors for each year since

1980. Names and positions were provided for validation, with the assurance that

they would not be published. Subsequent data sweeps were conducted in 1995 and

1998.

These efforts have resulted

in data for an average of 215 Fortune 500 firms for every year from 1980 to

1998. The longitudinal nature of the database allows us to compare the data for

any year with any other year since 1980, and allows the historical performance

of any responding firm to be studied on a variety of measures.

The Scoring System

Once we tabulated these

data, we devised a system to score each firm on their record for promoting

women to the executive suite. We weighted the pioneering efforts of firms in

the years 1980 to 1992 heavier than the efforts in later years. Two points were

assigned for each woman in a ”top 10” executive position for the

years to 1992, with one point for later years. One point was assigned for each

woman in the ”next 10” positions to 1992, and one half point for

later years. One point was given for each woman on the Board of Directors for

the early years, and one half point for subsequent years. Scores were summed

and firms were ranked in order. The 31 firms that scored the highest (the top

one-seventh) were then evaluated for profitability. Because the survey had

guaranteed anonymity to responding firms, we regret that those firms cannot be

named here.

Four Evaluations of Profitability

Because different

industries might prefer to use different measures of profitability, three

measures of profitability were used to evaluate each of the firms. Profits as a

percent of

revenues, assets, and stockholders’ equity were recorded for each firm, based

on data from the 1999 Fortune 500 list. In like manner, the equivalent figures

for the median Fortune 500 firm in each firm’s industry were recorded. Six of

the firms did not have data available for 1999 and were discarded, leaving 25

firms. The figures for the 25 remaining firms were then summed, and a mean

number calculated. The same was done for the industry medians.

In addition, a fourth

measure of profitability was taken. We determined whether the each subject firm

was higher or lower than its industry median counterpart. This was done in

order to expose the potential situation whereby strong figures for one

dominating firm might obscure a general trend in the opposite direction for the

majority of women-friendly firms within an industry.

Results

The results showed a clear

pattern. Fortune 500 firms with a high number of women executives outperformed

their industry median firms on all three measures. Furthermore, the firms with

the very best scores for promoting women were consistently more profitable than

those whose scores were merely very good.

On the measure of profits

as a percent of revenues, the 25 subject firms outperformed the corresponding

industry medians by 34 percent. The women- friendly firms averaged 6.4 percent

while the average of their industry medians was 4.8 percent. When taken

individually, almost two-thirds of the subject firms (66%) outperformed their

median counterparts.

On the measure of profits

as a percent of assets, the 25 subject firms outperformed the industry medians

by 18 percent. The women-friendly firms averaged 6.5 percent while the average

of their industry medians was 5.5 percent. When taken individually, 62 percent

of the subject firms outperformed their median counterparts.

On the measure of profits

as a percent of stockholders’ equity, the 25 firms outperformed the industry

medians by 69 percent. The women-friendly firms averaged 26.5 percent while the

average of their industry medians was 15.7 percent. When taken individually, 68

percent of the subject firms outperformed their median counterparts.

The diligent reader will

note that the results might be sensitive to the number of firms included in the

analysis. If one were to limit the subject firms to only the ”top 10

firms” for women (or ”top 15 firms” or ”top 20

firms”), the results would be somewhat different. In fact, further

analysis showed a direction consistent with the basic conclusion that firms

with a stronger record of promoting women are more profitable.

In other words, the results

of the ”top 25 firms” that are featured in this study are very

conservative. The results would be even more dramatic if a smaller set of only

the most friendly firms for women had been highlighted.

Indicated Action

It is important to note

that the correlation does not prove causality. While it could be concluded that

a firm’s long-term record of promoting women to high positions results in

higher than normal profitability, it could also be argued that firms with higher

profitability may feel freer to experiment with the promotion of women to high

levels.

One intriguing additional

explanation is that firms exhibit higher profitability because their top

executives have probably made smarter decisions. One of the smart decisions

that those executives have made is to include women in the executive suite, so

that the best brains are available to continue making smart, and profitable,

decisions for the firm.

However one interprets the

data, it is clear from multiple measures that there is a positive correlation

between the existence of larger numbers of women in the executive suite and

higher than normal profitability within an industry. Wise executives might well

keep this evidence in mind as they consider promoting talented individuals to

the executive suite.

References

Catalyst [1990]. Women in Corporate Management. Catalyst, New York. Various other studies are available from www.catalystwomen.org.

Driscoll, Dawn-Marie and

Carol R. Goldberg [1993]. Members of the Club: the coming of age of executive

women. The Free Press, New York.

Fortune [1999]. ”The

Fortune 500” vol.139 no. 8. April 26, 1999.